Revitalizing Singapore’s Stock Market: From Well-Intentioned Tweaks to Investor-Centric Reform

The Edge Singapore featured my article "AN INVESTOR-CENTRIC BLUEPRINT FOR SG’S STOCK MARKET" on 4 August 2025.

Revitalizing Singapore’s Stock Market: From Well-Intentioned Tweaks to Investor-Centric Reform

Singapore’s equity market is facing an escalating threat of marginalization. In 1H 2025, the SGX saw more companies exit than list, with only three IPOs against nine delistings—and another seven flagged for the second half of the year.

Regional competitors are pulling ahead: Hong Kong registered 44 IPOs (with 210 more under review); Malaysia posted 32 (on track for 60, leading Southeast Asia by listings and funds raised); China had 51 by June (targeting 100); and Indonesia 22 (expecting 66 for the year). SGX’s average daily turnover remains stagnant around S$1.2 billion, compared with Hong Kong’s S$29.4 billion. This underscores how SGX is being overtaken in both market activity and relevance.

This persistent gap threatens more than prestige. Unless deep-rooted structural challenges are tackled, Singapore’s shrinking market will increasingly deprive domestic firms and international investors of credible, liquid funding options and erodes Singapore's financial-center credentials.

MAS Responds: Good Intentions, Incomplete Solutions

The latest MAS package–S$1.1 billion through the EQDP for non-index stocks, expanded GEMS research funding, new ETF incentives, and an investor redress consultation–are constructive but address liquidity, not fundamentals. Together with earlier proposals, they treat symptoms, not root causes. Demand-side incentives alone can’t compensate for systemic issues: too few investable companies, low public float, and structural trust gaps in enforcement.

Structural Gap #1: Quality Deficit: Too Few Investable Companies

A fundamental supply issue—not a demand constraint

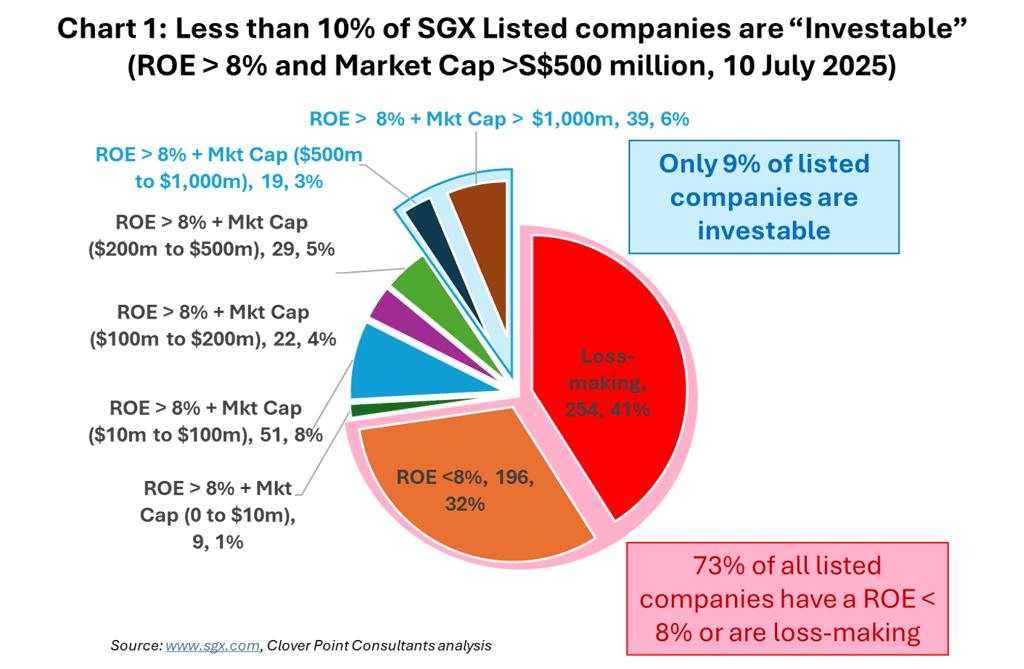

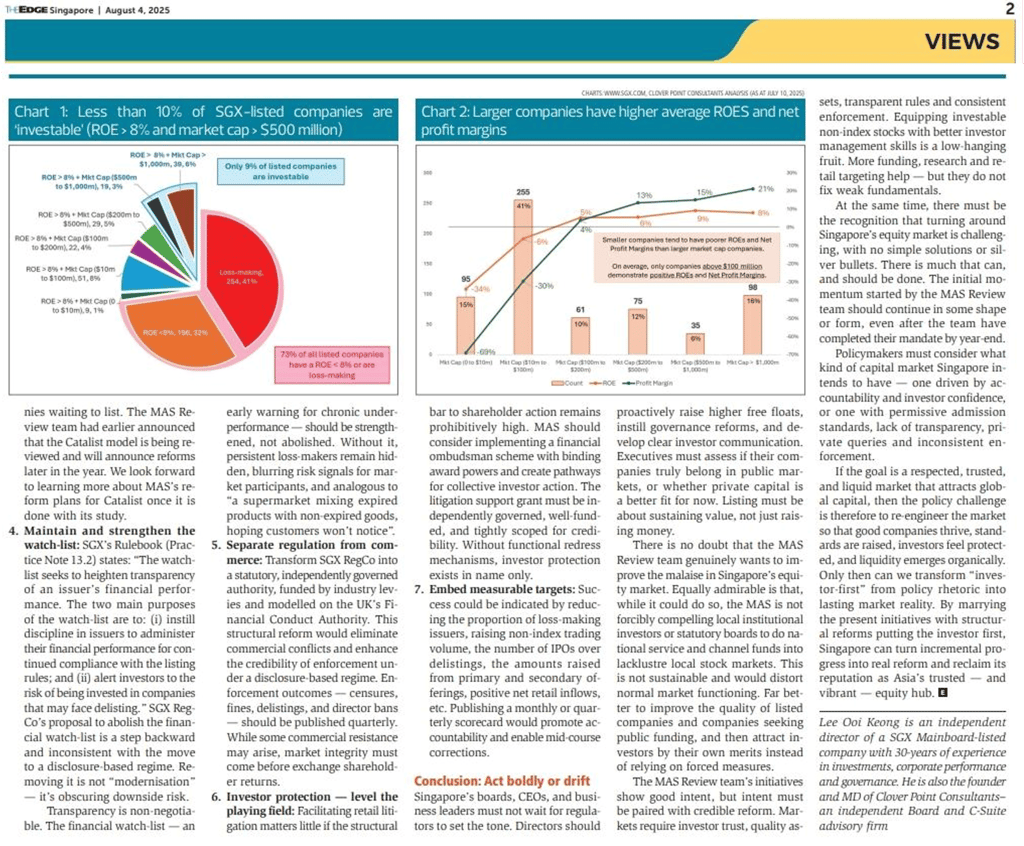

Of the 619 listed securities in July 2025, the fundamentals are poor. Only 569 are tradeable, with 50 suspended and 29 on the financial watch list. 41% are loss-making, 64% trade below book value, 73% have ROEs < 8%, and 66% are valued below S$200 million. This represents one of the lowest quality ratios among developed exchanges globally.

Hence, SGX’s trading is concentrated: 95% of all trading occurs in just 30 index stocks. MAS rightly targets mid-caps, but only 9% of all listings (58 firms) meet a typical institutional “investable” screen: profitability, ROE >8%, market cap >S$500 million. Excluding index stocks, only a mere 7% (44) non-index stocks qualify–an even narrower pool for new capital deployment.

A Dysfunctional “Growth” Board

The Catalist experiment has failed and clearly demonstrates the risks of premature listings. Of 204 Catalist counters, 57% are loss-making, 86% trade below their first-day close, and 40% have lost nearly all value. Most never transition to Mainboard; in fact, more underperforming Mainboard companies are demoted to Catalist than vice-versa.

The track record clearly shows that relaxed standards and conflicted sponsor-driven models (where sponsors are paid by the companies they oversee) create structural conflicts, drive persistent underperformance and poor accountability. Rather than broadening access, permissive admission standards have resulted in continuously poor performance.

The Risk of Premature Listings

The evidence is undeniable. Relaxed admission criteria whether on Catalist (no profitability track record, just 12 months of working capital cover) or SGX Mainboard (Regco’s proposed reduction of the profit test threshold to S$10 to S$12 million for Mainboard listings) do not reflect listing demands.

Small, early-stage growth companies lack the operational and governance maturity for public listing requirements. Public equity often destroys–not creates–value, especially given high annual listing costs (estimated at ~S$300–500k for Catalist, S$3–5 million for Mainboard).

Public equity is simply not the right funding option for most small firms. Private capital—venture debt, private credit, private equity, government grants— is a better pathway until scale and performance are established. For companies below the S$30 million profitability threshold, accessing public capital is akin to giving alcohol to children.

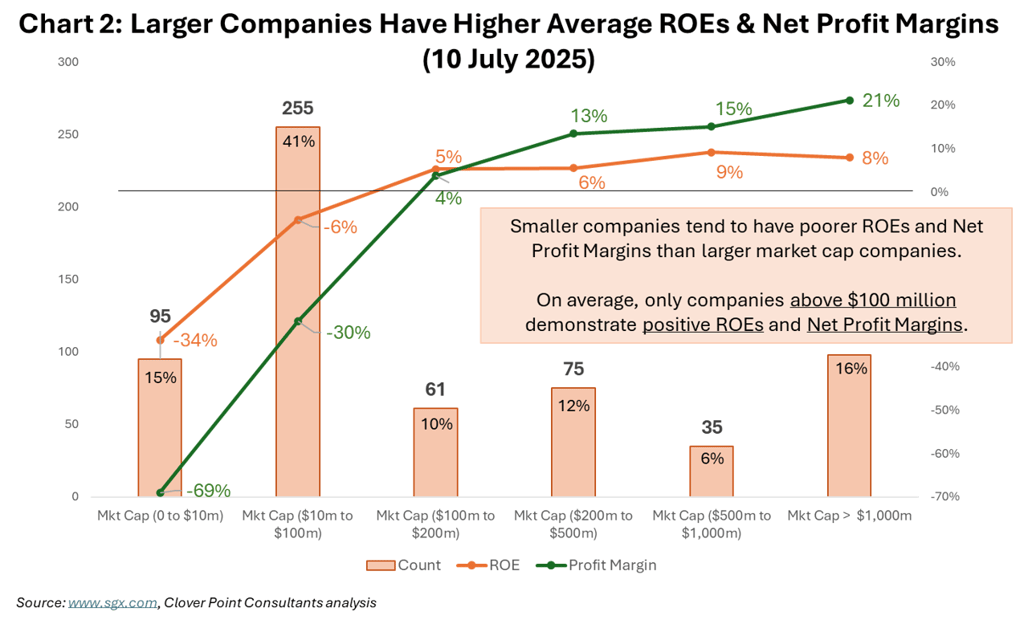

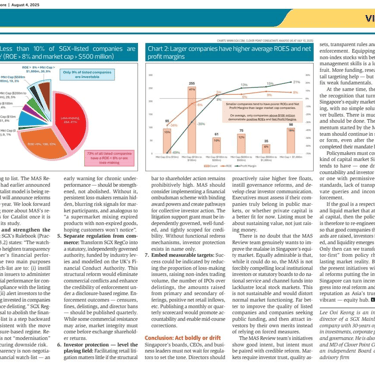

SGX’s own data confirms that, on average, smaller listed firms below S$100 million market cap are loss-making, with larger firms more likely to be profitable (see Chart 2).

Structural Gap #2: Liquidity Bottleneck: Too Little Free Float

Singapore’s 10% minimum free float is among the lowest globally—Malaysia and Hong Kong require 25%. Two-thirds of listed firms have free floats of less than 50% of their shares. Over 90% have block shareholders who exercise controlling power.

The irony is that in trying to “preserve control”, controlling shareholders also constrain their companies’ long-term value by limiting their own liquidity and trading depth. Ultimately, this restricts both institutional participation and retail trading. Hence, float scarcity concentrates trading in the largest names, reinforcing a two-tier market and choking the very mid-cap segment the EQDP seeks to nurture.

While some studies suggest little correlation between free float size and trading liquidity (observing that investor management capabilities correlate better with liquidity), it is a fact that asset managers invest in sizeable amounts. Without sufficient free float, asset managers will simply move on to other more liquid counters able to absorb their investments. Hence, EQDP’s focus on mid- and small-cap stocks is well placed in principle, but without increased free floats, its capital will struggle to find sufficient liquid opportunities.

Structural Gap #3: Enforcement Without Independence

Unlike retail consumers safeguarded by the Consumer Protection (Fair Trading) Act (CPFTA), Singapore’s investors lack a dedicated framework for redress.

While UK and Australia investors can rely on binding outcomes via the Financial Ombudsman Service (FOS) and the Australian Financial Complaints Authority (AFCA), Singapore investors must rely either on private litigation or regulatory enforcement by SGX RegCo—each of which is fraught with delays, legal cost, and concerns over independence.

SGX RegCo’s structure remains conflicted—a wholly-owned and fully-funded SGX subsidiary regulating its own fee-paying clients. This undermines true regulatory independence. The parallels with Catalist’s conflicted sponsor model is obvious for all to see: accountability is weakened when enforcement answers to commercial priorities. He who pays the piper calls the tune.

The lack of a financial ombudsman, collective action pathways and timely disclosure-based enforcement and the complexity of private litigation–often prohibitive in cost–under SFA Section 234 or Companies Act Section 216 leave retail investors at a disadvantage.

Effective disclosure-based regimes require stronger, not weaker, enforcement. The UK and US models demonstrate that robust enforcement is essential to maintain disclosure quality and investor confidence. Hong Kong’s Securities and Futures Commission routinely imposes fines and license suspensions on errant sponsors. Bursa Malaysia, which fined 179 directors RM32.4 million (S$9.2 million) between 2014–2020 for disclosure and governance breaches, is also SEA’s most vibrant stock markets. All these markets do not face any issues in attracting quality listings.

To be fair, both the Board and Senior Management of SGX cannot be blamed. As a listed entity, they have fiduciary responsibilities to maximize shareholder value. By that measure, the Board and SGX Senior Management should be applauded as SGX is one of the most profitable listed companies in Singapore with 44% net profit margins and ROEs of over 32%. As a listed entity, SGX cannot be faulted for prioritizing its financial goals, notwithstanding the current mixed-model exchange/regulatory framework in Singapore.

However, the same cannot be said of the regulators. The regulators’ role is to design and enforce a regulatory framework that enables market forces and participants to achieve their own respective goals and collectively enhance the overall functioning of the stock market to the benefit of Singapore’s economy, financial hub status, listed companies and investors. If the current financial framework is not performing to expectations, then we need to take a hard look and where necessary, make bold reforms to improve the situation especially when it is obvious that the status quo is not working.

Why MAS Measures Alone Fall Short

Against this structural backdrop, MAS’s latest package offers incremental—not transformative—relief.

The first EQDP tranche represents 0.12% of SGX’s S$900 billion capitalization and less than one day of trading turnover (about S$1.2 billion). Even full deployment of the S$5 billion envelope is less than five trading days or, assuming one-for-one co-investment with 3rd party investors, a 3% uplift in average daily value.

Asset-management credibility notwithstanding, liquidity injections of this scale cannot compensate for the structural deficits in investable float and quality. Without resolving listing quality and float size, EQDP funds may chase the same crowded stocks, recycling into already-liquid blue chips, and bypass the companies it was designed to help.

GEMS, though valuable in encouraging research coverage, can only drive meaningful analyst attention where institutional participation is possible. Research follows liquidity. Analysts will only cover counters where institutional investors can deploy capital at scale; that cannot happen while free float remains so tightly held. The ETF incentive is likewise helpful yet unlikely to succeed if the underlying shares trade in thin volumes. Without higher corporate quality and bigger free floats, enhanced research risks preaching to an absent audience.

The proposed recourse framework is a welcome start and addresses some genuine gaps but remains tentative. Without a statutory ombudsman and a defined budget, retail investors will continue to face high evidentiary and cost hurdles. Additionally, the legal burden of proving shareholder oppression through Section 216 of the Companies Act remains high and out of step with best practice.

An Investor-First Path Forward

The evidence suggests that Singapore can regain competitive edge only by coupling demand-side incentives with structural fixes.

Raise Standards and Enforce Listing Discipline: Retain the S$30 million three-year profit requirement and introduce a modest profitability or cash-flow threshold for Catalist. Rule 1315 already empowers SGX to compulsorily delist companies after six consecutive loss-making years. Enforced consistently, this would clear persistent underperformers, restore investor discipline, and stop the race to the bottom.

The idea that stricter standards deter listings is contradicted by Hong Kong’s experience: despite imposing higher thresholds, it remains Asia’s busiest exchange. Hong Kong’s success shows trust and quality drive volume—not permissive standards or incentives. Quality listings attract institutional capital and attract global interest.Free the Float: Aligning the minimum free-float requirement at 25% for new listings only, in-line with regional bourses, phased in over two years, would broaden the investable universe and magnify the impact of liquidity programs. This is the only way to broaden the universe for institutional capital, reduce controlling shareholder strangleholds, and make liquidity measures meaningful.

Review Catalist Model: There is an urgent need to reform Catalist. Sponsors need to be held accountable for governance lapses and regulatory breaches by the companies they supervise, but not for poor company performance, unless linked to sponsor negligence. These measures would significantly enhance the quality of companies seeking public funding. The UK LSE’s AIM Nominated Advisors (Nomads) and Hong Kong’s SFC IPO Sponsors scheme where negligent or errant sponsors are held accountable provide instructive models. Instead of scaring away potential sponsors and companies wanting to list, both the LSE and HKSE have no shortage of companies waiting to list.

The MAS Review team had earlier announced that the Catalist model is being reviewed and will announce reforms later in the year. We look forward to learning more about MAS’ reform plans for Catalist once they are done with their study.Maintain And Strengthen the Watch-List: SGX’s Rulebook (Practice Note 13.2) states that “The watch-list seeks to heighten transparency of an issuer's financial performance. The 2 main purposes of the watch-list are to: (i) instill discipline in issuers to administer their financial performance for continued compliance with the listing rules; and (ii) alert investors to the risk of being invested in companies that may face delisting.”

SGX RegCo's proposal to abolish the financial watch-list is a step backward and inconsistent with the move to a disclosure-based regime. Removing it is not “modernisation”— it’s obscuring downside risk.

Transparency is non-negotiable. The financial watch-list—an early warning for chronic underperformance—should be strengthened, not abolished. Without it, persistent loss-makers remain hidden, blurring risk signals for market participants, and analogous to "a supermarket mixing expired products with non-expired goods, hoping customers won't notice ".Separate Regulation from Commerce: Transform SGX RegCo into a statutory, independently governed authority—funded by industry levies and modelled on the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority. This structural reform would eliminate commercial conflicts and enhance the credibility of enforcement under a disclosure-based regime. Enforcement outcomes—censures, fines, delistings, and director bans—should be published quarterly. While some commercial resistance may arise, market integrity must come before exchange shareholder returns.

Investor Protection: Level the Playing Field: Facilitating retail litigation matters little if the structural bar to shareholder action remains prohibitively high. MAS should consider implementing a financial ombudsman scheme with binding award powers and create pathways for collective investor action. The litigation support grant must be independently governed, well-funded, and tightly scoped for credibility. Without functional redress mechanisms, investor protection exists in name only.

Embed measurable targets. Success could be indicated by reducing the proportion of loss-making issuers, raising non-index trading volume, the number of IPOs over delistings, the amounts raised from primary and secondary offerings, positive net retail inflows, etc. Publishing a monthly or quarterly scorecard would promote accountability and enable mid-course corrections.

What Should Boards and CEOs Do Now?

Singapore’s boards, CEOs, and business leaders must not wait for regulators to set the tone. Directors should proactively raise higher free floats, instill governance reforms, and develop clear investor communication. Executives must assess if their companies truly belong in public markets, or whether private capital is a better fit for now. Listing must be about sustaining value, not just raising money.

Conclusion: Act Boldly or Drift

There is no doubt that the MAS Review team genuinely wants to improve the malaise in Singapore’s equity market. Equally admirable is that, while it could do so, the MAS is not forcibly compelling local institutional investors or statutory boards to do national service and channel funds into lackluster local stock markets. This is not sustainable and would distort normal market functioning. Far better to improve the quality of listed companies and companies seeking public funding, and then attract investors by their own merits instead of relying on forced measures.

The MAS Review team’s initiatives show good intent, but intent must be paired with credible reform. Markets require investor trust, quality assets, transparent rules and consistent enforcement. Equipping investable non-index stocks with better investor management skills is a low-hanging fruit. More funding, research and retail targeting help—but they don’t fix weak fundamentals.

At the same time, there must be the recognition that turning around Singapore’s equity market is challenging, with no simple solutions or silver bullets. There is much that can, and should be done. The initial momentum started by the MAS Review team should continue in some shape or form, even after the team have completed their mandate by year end.

Policymakers must consider what kind of capital market Singapore intends to have—one driven by accountability and investor confidence, or one with permissive admission standards, lack of transparency, private queries and inconsistent enforcement.

If the goal is a respected, trusted, and liquid market that attracts global capital, then the policy challenge is therefore to re-engineer the market so that good companies thrive, standards are raised, investors feel protected, and liquidity emerges organically. Only then can we transform “investor-first” from policy rhetoric into lasting market reality. By marrying the present initiatives with structural reforms putting the investor first, Singapore can turn incremental progress into real reform and reclaim its reputation as Asia’s trusted – and vibrant – equity hub.

Written by:

Lee Ooi Keong

25 July 2025

Brief bio: Lee Ooi Keong is an Independent Director of a SGX Mainboard-listed company with 30-years of experience in investments, corporate performance and governance. He is also the founder and MD of Clover Point Consultants–an independent Board and C-Suite advisory firm.

Like this article? Follow me on Linkedin and read my latest posts, articles and more!